Abstract - this is a preprint version

The purpose of this paper is to discuss the outcomes of the Fitzwilliam Museum’s Arts and Humanities Research Council funded (AHRC) Creative Economy Engagement Fellowships, a practise driven research and development programme and knowledge transfer activity. These four short term posts (6 months in length) aimed to provide the opportunity for Early Career Researchers (ECRs) to work with small/medium enterprises (SMEs) as creative industry partners to explore the interface between 3D printing and associated educational technologies and museological practices, and the public engagement programmes of the University of Cambridge’s (UCAM) principal art museum. The overall shape of this research activity was developed as a rapid response to an internal funding call at UCAM. It was designed by the Principal Investigator (Daniel Pett) and the Museum’s Research Facilitator (Dr Joanne Vine) to approach 4 areas of interest for the museum. These were:

- the use of low cost, replicable 3D scanning to make the Fitzwilliam Museum’s collection available in multiple formats;

- to work with an educational technology start up to leverage 3D technologies;

- to see how the creative industry partners could exploit these assets and create knowledge transfer opportunities for the researcher;

- and finally how these methods could be reproduced and employed by peer institutions.

Each fellow was recruited to work on a specific project, developed in conjunction with the Museum’s staff and the creative industry partner. This novel approach had not been implemented before in the UCAM museums and provided significant individual contributions to original research (Egyptological studies), major exhibitions (Feast and Fast (F&F)), prototypes for the Being an Islander (BAI) exhibition (now delayed by Covid 19), and a large-scale conference in 2019 held at the Judge Business School.

Introduction

The heritage sector has often been at the forefront for trialling new or emerging technology and is championed as having the potential for exciting or engaging case studies. 3D printing is a prime example of a technology that has been an early focus of experimentation in the museum and heritage sector (Coates 2019) with early adopters presenting the potential as early as 2014 (Reilly 2015).

The potential of these technologies, techniques and associated interventions led to the Fitzwilliam Museum (FM) obtaining funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Creative Economy Engagement (CEE) scheme (AH/S012583/1) to establish four post-doctoral fellowships (each for 6 months in duration) - identified as CEEF by the museum.

These fellowships aimed to explore how the UCAM’s principal art museum could expand its digital armoury (with a focus on 3d printing, modelling and the use of educational technology) and in-gallery tactile experience and enhance the skills and knowledge of its permanent workforce, whilst focusing on existing projects (exhibitions such as F&F and BAI, research projects such as Egyptian Coffins and Do Not Touch).

The Museum’s partners in this endeavour were Museum in a Box (MiaB) and ThinkSee3D (TS3D); both SMEs use 3D materials derived from cultural heritage to provide new and meaningful interactions for museum and non-museum going audiences.

To enable this programme of research, three fellowships were assigned a specific practise based research programme of activity, with the remaining fellowship focusing on existing practices and theory and to provide guidance for the other fellows and ideally the museum/heritage sector on the use of 3D printing. The fellowships were divided into:

- CEEF1: Development of guidance for the museum sector for the use of 3D replicas.

- CEEF2: Development of 3D interventions to engage diverse audiences with the Egyptian Coffins research via a ‘Pop-Up Museum’.

- CEEF3: Development of prototype subscription models for Museum in a Box and an intervention for the F&F exhibition.

- CEEF4: Development of a prototype Museum in a Box collection for the BAI exhibition.

Each Creative Industry partner was tasked with sharing expertise, methods and insights about their work with the fellows to develop their own museum based intervention driven by the technology set they employed. The researchers’ projects were influenced by current industrial and academic challenges in the heritage sector, which ‘forms an integral and vital part’ of the creative economy’, as described within the AHRC Heritage Priority Strategy document (AHRC 2018) and aimed to enhance the Mission and guiding principles of FM public engagement activity.

Through three of these fellowships, 3D prints were offered to create tactile experiences of museum objects, with the concept of storytelling, narrative discussion and development of new content as a key component. Storytelling is at the heart of the mission for many museums (Adler & Johnsson 2006; Bedford 2001), increasingly this is via digital means through the employment of emergent digital technology such as 3D modelling and printing, immersive experiences (Augmented/Virtual Reality), mobile applications, and online explorations (for example, see Wong 2015). Storytelling not only enhances the emotive engagement of audiences but allows us new ways of opening up and sharing dialogues around archaeological data. In this sense, we are using archaeological imaginings to produce different forms of knowledge via different ways of sharing (Tringham 2019: 339-340).

Making museum data, collections and research both available and palatable to researchers and members of the public is a challenge all cultural heritage institutions face and will continue to face in this rapidly changing technologically-driven world. This interface with the public/academic becoming an increasingly urgent and imperative consideration in relation to discussions around the need for decolonisation and multivocality in the museum’s collections as a means to opening up new dialogues about the past and the use of these technologies could be a vital aid in this work.

CEEF1: 3D replicas within the UCM

This project was led by Catriona Cooper, working in conjunction with TS3D and the FM’s ‘Do Not Touch’ Project, and considered the development of guidance to best practice for museums who are considering working with 3D prints. The potential for museum collections to use 3D printing has been considered both formally (Di Giuseppantonio Di Franco et al 2015) and there is a wealth of informal (anecdotal) evidence as to its potential (including that developed by our creative industries partner, TS3D).

Tactile experiences and replicas (Cormier 2018), are not a new development to the museum or heritage sector: early vestiges of the museum in the 17th century incorporated touch and “manual investigation” as an integral element to understanding objects (Classen 2005). However, modern museum practices sanitised the museum experience, not only limiting our understanding of collections to a uni-sensory visual experience (Candlin 2008), conditioning us into an understanding that touching in museums is expressly forbidden (Bacci and Pavani 2014).

The turn of the century, saw a return to object handling in museums as part of learning and engaging experiences and it is noted that touching objects allows us to understand the world around us, objects and collections, in new ways and it is these experiences that enchant and excite visitors (Levent and McRainey 2014).

The introduction of these experiences is not straightforward; curators and conservators have pertinent concerns about the impact these experiences will have on the objects in their care. The successful introduction of long term, mediated, permanently located object handling desks within large museums, for example the British Museum (2008) has recently incorporated 3D prints (for example, at the Sunken Cities exhibition of 2016) created by Creative Industry partner TS3D (Dey 2018). These handling desks are often created and maintained via large museum institutional privilege, the allocation of resources to facilitate engagements through their permanent and volunteer staff puts this type of intervention beyond the reach of smaller museums - an extension of the Digital Divide.

This project therefore focused on the adoption of 3D prints (created by TS3D) as part of un-facilitated engagements (i.e. without a member of staff or volunteer actively engaged with the objects) with the intention that a guide to best practice would be produced following observational analysis of two 3D prints of sections of objects installed in the Antiquities galleries of the FM in late 2019 as part of the ‘Do Not Touch’ project led by Pett and Helena Rodwell. Data was gathered during two hour sessions over four days, both during the week and weekend, and at different times of day in line with the project protocol.

The first 3D intervention is an extract from an ancient Egyptian shrine built by King Thutmosis III at El Kab (E.40.1902). Dedicated to the goddess Nekhbet, the outer walls of the shrine are inscribed, but the low levels of lighting in the gallery make the inscriptions harder to identify visually.

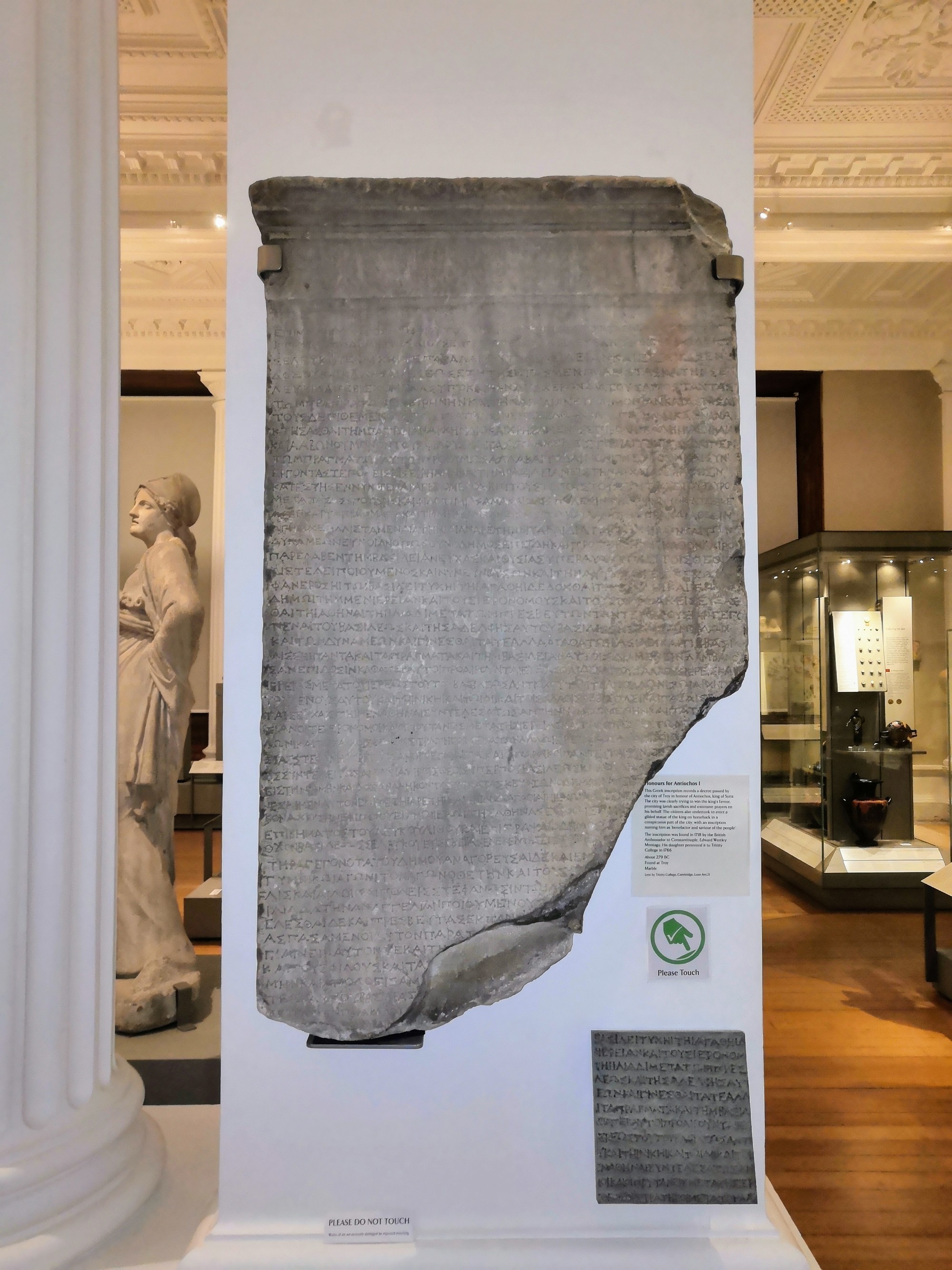

The second 3D print is taken from a large marble slab carved with a Greek inscription of the Honours for Antiochus (Loaned from Trinity College, Cambridge Loan Ant.21) hung facing away from the centre of the room, often overlooked by visitors.

A goal of the ‘Do Not Touch’ project was to discover whether there was potential for the use of 3D prints, to evaluate the impact on visitor experience and behaviour and provide actionable insight for the FM’s collections care team. An existing hypothesis was present within ‘Do Not Touch’; would the provision of an alternative tactile engagement satisfy a visitor’s needs for haptic understanding and help discourage non-permissive touching of objects.

These objects were not displayed under optimal conditions - minimal temporary signage was placed next to the 3D objects and demonstrated some of the traditional museological views that needed to be overcome to facilitate this work. There was a green glyph icon showing a finger pointing towards the print encouraging visitors to touch, but the curatorial/interpretation team made a deliberate decision to provide no explanation/interpretation about the 3D prints. An opportunity exists to test the effect when enhanced interpretation is provided.

A small scale evaluation was undertaken. 115 individuals or groups (to be included in the data capture individuals or groups had to walk directly past the 3D print) were observed over several sessions in August/September 2019, of which 73 individuals or groups did not notice the print. Of those who did observe the print a further 22 did not engage with the print - leaving only 20 visitors who did interact. The small sample size can therefore lead to suppositions and insights gained from these interventions to be seen as not having significant impact, compare to the research conducted by Di Franco (Di Giuseppantonio Di Franco et al. 2015) at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, when she worked on the Star Carr 3D material (also produced by TS3D).

Low level responses were elicited from the sample, for example "that is nice" and "but we can actually feel that". In four instances individuals initiated the rest of their group into engaging with the prints promoting extended discourse and therefore social interaction around the artefacts and print. Interactions like these are indicative of a positive visitor experience through collaboration and social engagement discussed by Katifori et al (2016).

The print of the ‘Honours for Antiochus’ was placed away from any interpretation of the artefact below the object, out of the sightline of the majority of visitors, but ideal for children and those in a wheelchair.

The print from the Egyptian shrine built by King Thutmosis III at El Kab was placed much closer to the intended view of the artefact, but below the object, so a cursory glance could miss the intervention easily. The artefact itself is on a thoroughfare so many visitors do not stop to engage. In both instances the prints were deliberately deployed by FM curatorial and interpretation staff without full explanation about what they are or why they were placed there. The process brought out the need for advocacy and the need to demonstrate the additional value of these interventions.

These limitations highlight the need for museum staff to work in consultation with the fabricator to ensure that the prints are produced and deployed in-gallery most effectively. Simple insights obtained from this observational analysis made obvious recommendations to the FM interpretation team with the key concept being the paramount importance of object placement (much in the same vein as the original piece of work).

Derived from this, the following workflow is suggested for museum staff to develop an effective/affective experience using 3D prints to facilitate interaction and understanding of objects on display without jeopardising the conservation and protection of the artefacts.

- Selection: From the initial consideration of introducing a 3D print into a gallery, it is vital to consult all relevant stakeholders and have a clear understanding why you are undertaking this work: is it in response to visitor feedback? Largely this will be staff or volunteers who would be directly involved in oversight of and public engagement within the altered environment; curators, front of house, education and learning, development, trustees, senior management and registrars. While curators and conservators might have a strong understanding of the objects that would benefit from additional interpretation or protection from un-facilitated touching, a gallery attendant will have practical knowledge about how visitors move through the space, if the objects are of particular interest to visitors and current interactions. This type of discussion will ensure objects that would most benefit of an installation of this type will be prioritised and a change to the gallery routes will not disrupt current visitor flow.

- Specification: Once museum staff are in agreement on their selection, a discussion with the maker is important prior to commissioning. It is important to note that there is a wide variation between what a ‘3D print maker-artist’ and ‘3D print maker’ does: it is crucial to be clear if you are looking for a high-quality 3D print that a maker-artist would be more appropriate; if you are looking for lower-quality, higher-volume prints, a 3D print maker might be more appropriate.

- Installation: The print needs to be installed in close association with the original, visible to all visitors and easily accessible.

- Interpretation: Interpretation needs to go beyond the label of the artefact being modelled and needs to include information about the print; why it is there and what it is. Without information the tactile engagement will not return the visitor to the original and can also be used to engage in wider interactions between visitors considering the making process and technology. Further appropriate signage indicating which objects can and cannot be touched needs to be clearly displayed.

These recommendations have since been deployed with the commissioning of a 3D print of a fossil at the Polar Museum and will be used in future at the FM. As with all deployments of new technology the key is to consider not just the advantages and potential in producing a 3D print but the wider impact it might have on the gallery: financial, experiential and practical. Through this work package of the fellowships, the museum significantly enhanced its understanding of the use of 3D printing technologies and we built on the experience of TS3D (Dey 2018). Insights gleaned from working with him as a creative partner included:

- Additive printing It is not always the best option for creating 3D replicas. Frequently it maybe, but many factors influence choice and these include budget, material and final use;

- It is often a more rapid means for replication of complex objects, it can remove the need for highly skilled crafts people, reduce costs and produce derived digital 3D model(s) which might be used for multiple purposes - virtual and augmented reality, computer gaming;

- It can often negate knowledge loss in the making process for replication of cultural artefacts;

- It can often be the starting point for more traditional craft work to occur. A 3D print could be used to create moulds or lasts for the production of casts.

Out of the 4 fellowships, this project did not deliver all of its final outcomes due to the researcher obtaining a full-time, teaching focused role at Royal Holloway University, for which the opportunity was vital for progression from precarious employment to security.

CEEF2: The Pop-Up Egyptian coffins project

The FM’s interdisciplinary ancient Egyptian coffins project has been running since 2014, with a team of Egyptologists, conservators, a pigment analyst, an expert in historical painting techniques, an ancient Egyptian woodworking specialist and a consultant radiologist. This research project harnessed the application of advanced imaging techniques such as Computed Tomography (CT) scanning and X-radiography, to reveal unprecedented insights into how coffins were made and decorated, the ancient Egyptian economy and attitudes to death and the afterlife.

In 2016, this research culminated in a major exhibition and publication, Death on the Nile: Uncovering the Afterlife of Ancient Egypt, which was visited by 91,782 people. Despite this impressive figure, audience demographics identified an alarming gap in the exhibition’s visitation among socially- and economically-diverse visitors. In a survey conducted with 334 exhibition visitors, 67% were educated to degree level or equivalent and predominantly resided in the local Cambridge area.

As part of an institution-wide effort to remedy statistics like this, the FM Egyptian coffins team developed a ‘Pop-Up’ Museum – a community outreach initiative where researchers bring real museum objects, craft replicas, hands-on activities and digital experiences into the heart of communities who might not otherwise have access to our research (figure 2).

This is done through unexpected interventions – namely the appearance of ‘Pop-Ups’ in locations where people would not normally expect to have a cultural encounter, for example in a pub, supermarket, shopping centre and food bank. This concept has its origins in an outreach project initiated at the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (MAAS) in Sydney, Australia in 2012 as part of the exhibition Faith, fashion, fusion: Muslim women’s style in Australia. Exhibition curators, Jones and Pitkin, travelled into the heart of Sydney’s Muslim community (approximately 1 hour from Sydney’s Central Business District) with real objects from the collection, activities and giveaways in order to broaden their reach with their research and strengthen community relationships.

With the support of the Arts and Humanities Impact Fund (AHIF, UCAM) and the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF, UCAM), we were able to pilot this concept in two regions: the Fenland town of Wisbech in Cambridgeshire and also in Cairo and Damietta, Egypt. Wisbech was selected owing to its geographically-isolated location and reported status as one of the most deprived towns in the whole of the United Kingdom (National Conversation 2017). About one-third of residents are non-native English speakers from Eastern Europe; there is a high rate of unemployment and many of those with jobs are on the basic minimum wage. According to the 2011 census, 35.1% of Wisbech residents are without qualifications and 19.1% are estimated to have skills at entry level or below for literacy (Cambridgeshire County Council 2016). Compare this to the gilded academic status of Cambridge!

A key challenge presented by the ‘Pop-Up’ concept was how we would best engage diverse non-academic audiences in culturally underserved areas; how would we make the content accessible, relevant, multilayered, tactile and visually stimulating? How could we get people to invest their time in us? And, how could we encourage them to follow-up on their experience with further engagement in the subject of ancient Egypt and/or by visiting a museum? Given that our research angle was already heavily focused on industry and the handmade – something that many people, particularly those already involved in a trade, can relate to – we approached our content offerings as follows:

- carpentry;

- pigments and painting and;

- ancient Egypt and museums more generally.

We also needed to ensure that our content was flexible enough to be adapted to different learning levels and abilities.

Thus, our ‘Pop-Up’ offered the following experiences:

- The display of a genuine 3000-year-old fragment of a yellow coffin face and hand in a secure, airtight showcase

- A selection of craft replica tools from ancient Egypt (similar to those used today), also displayed in a secure, airtight showcase

- Craft replica joints available for handling

- A painting activity where visitors can make their own replica ancient Egyptian paint brushes and use ancient-inspired pigments

- iPads linked to the Fitzwilliam Egyptian coffins website

- A3 colour photographic visual aids to facilitate conversations about CT scanning, X-radiography in coffin studies, and contextual images of the Fitzwilliam Museum and relevant sites in Egypt

- Free giveaways, including the Museum’s publication ‘How to make an Egyptian coffin’ (Dawson 2019), bookmarks, and scarab beetles for children

The opportunity to work with creative industry partner TS3D therefore opened up a new world of possibilities for our ‘Pop-Up’ project, particularly in terms of the ability to offer more tactile and visually arresting experiences. From the outset of the project, for example, we envisaged producing some type of interactive experience where visitors could actively assemble and disassemble a coffin, or parts of a coffin, in order to better understand wood construction and joinery. It would also serve as a visual aid to help illustrate the types of technical terms we might use when explaining how a coffin is made (for example, dowels and mortise and tenon joints) and help to give participants a sense of accomplishment through successfully putting it back together. Since the element of portability was important for our project, we selected a small rectangular box coffin from the Museum’s collection believed to have been made for a dog called Heb (figure 3: left). Given that TS3D specialise in 3D printing, it seemed instinctive for us to first consider recreating the dog coffin in the form of a 3D print.

The production costs of a 1:1 scale coffin made in durable materials for repeat handling, such as gypsum, were instantly an issue. To be affordable, our 3D print would need to be made considerably smaller, raising questions around the importance of authenticity and the multi-sensory experience in 3D printing. According to a 2017 study (Wilson et al 2017) on visitor attitudes to touchable 3D printed replicas in museum exhibitions, for example, “many interviewees” stated that:

“…the more authentic and realistic looking that the 3D prints were, the better”.

By 3D printing a smaller version of the dog box coffin, therefore, authenticity would be significantly lacking—not only in terms of size, but also material (you cannot 3D print in real wood, but in a composite form of wood fibre and Polylactic acid (PLA)), weight, texture and smell (the original coffin is made from the sweet smelling Cedrus libani, or Lebanese cedar tree). Something else that has always been integral to our research is the way in which we can learn about ancient processes and how things are made through recreation and reproduction.

Thus, to capture all these elements, we commissioned Dr Geoffrey Killen, a specialist in ancient Egyptian woodworking techniques, to produce a 1:1 scale craft replica of the dog box coffin using the same species of wood (figure 3: right). This approach enabled us to keep truer to the original coffin in terms of its specifications and gain a better understanding of the mindset of the ancient carpenter who constructed the coffin, including a deeper appreciation for how much time and care went into producing such a coffin for a pet dog. Killen estimated it would have taken 4-5 days to produce, something we could not have determined so easily from a downscaled 3D print. A craft replica also offered participants to the ‘Pop-Up’ a more multi-sensory experience, particularly in terms of its materiality, weight and the strong, sweet smell that emanates from the freshly cut Cedrus libani tree—a characteristic which often stimulated much discussion with participants around the different types of native and imported timbers used in ancient Egypt. The only feature Killen was unable to reproduce through his craft replica was the warped effect of the wood caused by thousands of years of ageing and changed environmental conditions, which a 3D print could have generated. However, through photographs and a digital 3D model we were easily able to point out this difference to visitors.

Although authenticity and process was important for us, we wanted to know if this was the same for participants in our ‘Pop-Up’ Museum. We therefore conducted an evaluation where we asked visitors what they preferred—that is, real objects, replicas or digital experiences. The majority of respondents indicated that they preferred to see real objects because it “invoked a sense of awe”, but in the unprompted responses many people specifically pointed out how much they enjoyed “chatting with real subject specialists”. Owing to lower than anticipated literacy levels among respondents, the evaluation study took on three iterations. The first was a written survey completed by 20 respondents between March-April 2019. The second was a visual chart and verbal questionnaire completed by 12 respondents between May-June 2019 and the third was an observation-tracking study.

We conducted observations with 30 participants, tracking their engagement with the different components of the ‘Pop-Up’ to see where people spent the most time. Considering the role our facilitation played in this process, and the nature of the hands-on activities, it is perhaps not surprising that participants spent most time talking to subject specialists followed by the painting activity. Another later addition to our evaluation, prompted by the diverse social chats we had with many participants, was a wellbeing study where we invited people to share how they felt both before and after their encounter with the ‘Pop-Up’ Museum. In almost all cases, participants reported feeling an elevated sense of happiness and inspiration after engaging with us.

In turn, what became the main focus of our collaboration with TS3D was the production of a digital 3D animation recreated from its CT scans of a 21st Dynasty coffin box belonging to a high official named Nespawershefyt (figure 4).

This animation takes people beyond the surface of the coffin’s decoration to better understand what lies beneath using CT scan technology – for example, the number of pieces of wood used in its construction, how they are joined together and how we can identify reused pieces of wood from other objects, including other coffins. Visitors ‘fly-through’ the coffin to see how it was assembled with narrated commentary and subtitles (in English and Arabic - which were produced by our Arabic speaking associates). People also have the ability to extend this experience beyond the ‘Pop-Up’ Museum by accessing the animation via the Fitzwilliam Egyptian Coffins online resource on any Internet enabled device. This digital resource has since been used within the Museum’s GCRF funded work with the Egyptian Museum Cairo and its ‘Pop-Up’ work with the Wisbech Museum and beyond. The bilingualism and visual nature of this resource provides an ideal teaching aid, supplementing the other digital content (Pitkin et al 2019) presented on the dedicated coffins website.

This animation pushed the boundaries for TS3D in terms of production time (a relatively new offering for TS3D), but also offered new ideas for the manufacture of their large-scale 3D prints. In particular, Dey (pers. comm) admits to gaining an intimate understanding of ancient Egyptian coffin joinery from this project and how dowels and mortise and tenon joints might be one solution to connect large-scale 3D prints, such as dinosaur bones and skeletons. This would consequently help to expand TS3D’s capabilities and market range in 3D printing if he were to trial this in the future.

While Nespawershefyt’s inner coffin box is now in a ready state to be 3D printed, at least for this project it has been shown how craft replicas can offer alternative experiences to 3D prints, particularly in terms of their multi-sensory dimensions, authenticity and enhanced academic understanding of ancient processes of production. They also offer another way of preserving what is gradually becoming the endangered slow crafts movement of making things by hand. But, the experience of a craft replica can certainly be heightened using a digital 3D model by allowing visitors to compare and contrast the two examples when portably displaying the real object is not an option.

CEEF3 & CEEF4: ’The Fitz, but in Bits’

A rare cheese; compostable sanitary towels; tailored shirts; glittery nail polish; and gluten free snacks for toddlers: just a few of the interests (or aspirations) catered to through subscription boxes. But if these boxes can cater to both the easily-left-off-the-shopping list and to the connoisseur’s prize, then why not try creating a version for museums? After all, the museum is a place for everyday access to the extraordinary.

To this end, we created and tested a prototype of a subscription box service for 3D printed replicas of objects in the FM, building on the technology created by MiaB. The test audience comprised eight adults and two children. All were based in Cambridgeshire or the London suburbs so that they could easily attend evaluation sessions at the Museum. By developing small, themed collections of low-cost 3D printed objects and paper materials for consumers to use with MiaB, we posited that we could increase the reach of the Museum’s collections as well as attract new and more diverse audiences to the museum itself. Abi L. Glen, the project’s lead, worked alongside curatorial staff and our creative partner, MiaB founder George Oates. The project involved collaborations with a local arts collective, voice actors, and historians, with the prototype collection themed around the FM's major exhibition, Feast & Fast: the art of food in Europe, 1500-1800 (original pre Covid 19 run - 26th November 2019 - 26th April 2020).

The project was broadly divided into two tasks: producing the physical boxes, and producing their intellectual content. Developing a complete prototype box involved the design and/or procurement of: postal packaging, branded mailer sleeves, printed ‘menus’ (displaying the copyright information for each museum object), and collections of 3D printed objects/postcards with NFC stickers attached. Developing the intellectual content of the boxes meant meeting with collections staff to identify suitable objects; researching objects’ background; writing copy for the recordings; acquiring voice actors, and recording appropriate material. Once this was acquired, each NFC sticker was encoded with the appropriate audio file, using the MiaB content management system.

In order to produce 3D models, each fellow was given facilitated training in photogrammetry and the basics of Agisoft’s MetaShape. A long photogrammetry session took place during the official preparatory FM exhibition photography for a mock-Baroque feast. Building the models in the software was the project of several months: the complicated nature of the subjects meant that we needed to fine-tune the models multiple times before they could be viable prints; for example, the lobster used in the feast had trailing tendrils, thin and translucent sections and hard to capture areas.

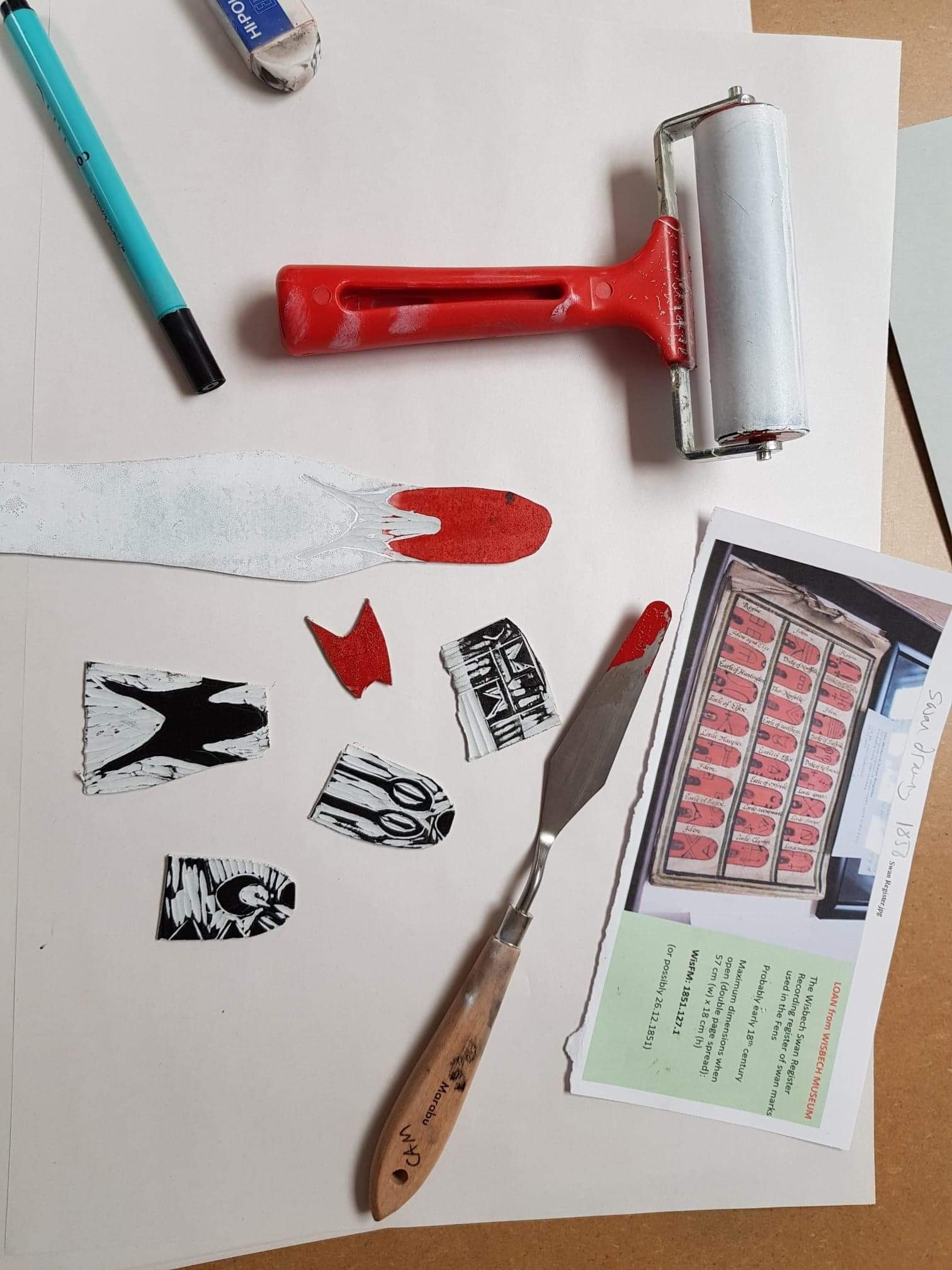

Outsourcing the design of the sleeves was important not only in aesthetic terms, but also to fulfil one of the AHRC’s aims: to stimulate the local creative economy. Local artists Cambridge Art Makers designed and made custom linocut sleeves for the mailer boxes (each limited-edition print was then wrapped in vellum to protect it during transit), based on the FM's visual language and the Wisbech Swan Register (figure 5: left and centre).

To produce the box’s content and to identify suitable models and research outputs to inform the design of our first collection, we worked closely with Dr. Victoria Avery, co-curator of the F&F exhibition. Once the boxes were complete, they were sent to each member of our test group through Royal Mail. Each member returned the enclosed feedback form, with questions designed to assess their experience of ‘unboxing’. Because sending each member a MiaB would have been prohibitive both in cost and inventory terms, instead these individuals were invited to the FM for a recorded assessment of their reaction to using their collection on a MiaB.

The most successful outcome was the design with the mailer sleeves which attracted widespread commendation, and each arrived at its destination more or less intact (some minor scuffs to the vellum notwithstanding). Positive feedback from the test subjects included ‘beautiful, enticing, neat’; ‘easy access, quality wrapped, pretty’; and ‘elegant, trim’. All subjects confirmed that the mailers fit through their post box; ‘a very good size of parcel’. One of the project’s aims was to assess reaction to a number of different delivery styles for the copy: male/female voices, curatorial/‘lay’ delivery, educational/humorous. Thanks in large part to the skill of the voice actors recruited, these categories were represented in the final product.

There were a number of production and supply delays throughout the process, for example after the artists had completed custom-printed sleeves for the mailer boxes, the company who supplied the boxes withdrew the product from sale. This necessitated the commission of custom boxes in that size, but cardboard is not an exact science, and the final mailer boxes were both over-budget and imperfectly dimensioned. While we had success with MOO in the production of attractive and expediently delivered printed media, this was not the case for the 3D printed objects.

Initial plans to utilise UCAM Dyson Lab 3D printers were not possible due to purchasing, access and logistical reasons; we could not use TS3D due to procurement problems, and therefore we used a USA based print-on-demand company Shapeways. The 3D printed lobsters we ended up with were of excellent quality; however, our original models for a partridge pie did not pass the company’s strict quality standards (due to the thinness of featured sections). Without time to remodel, we were forced to forego this element of the box. Ultimately, these delays meant that a number of our original test subjects were unable to participate in assessment within the new timeframe.

The test study’s participants had mixed reactions to being asked to assess the objects without any further context. Some found the initial engagement ‘intriguing’ and ‘inviting’; others commented that they were disappointed, claiming that ‘at the moment, it seems very detached’. There was also some confusion regarding the second stage of evaluation; some subjects felt that future recipients would need ‘a little more briefing as to how they were supposed to use the objects’. This could be simply rectified by producing a simple document for inclusion in the box, explaining the process (or indeed streamlining the process altogether). To demonstrate the success of this project, the exhibition team installed 3 boxes within F&F for the duration of the exhibition (26 November 2019 - 26 April 2020) (figure 6).

The ‘Wisbech Swan’ design caught the eye of the curators: and shop staff alike; their work was hung in the ‘creative zone’ of the exhibition space above the installation of the boxes. The artists were also commissioned to produce a limited run of art prints, cushions, and scarves for sale in the museum shop during the exhibition. The project has thus increased their visibility, profit and platform within the Cambridge community and beyond (the exhibition was predicted to attract 80-90,000 visitors, but realised 61,254 over two segments interrupted by Covid 19).

Through the installation of these commissioned pieces, the creative industry partners (the artists, and MiaB) gained an unexpected larger shop window showcasing the outputs of digital humanities research projects within the museum and potentially reach many thousands of visitors.

The outcomes of this project were trialled within a clinical setting, using extra funding from University of Cambridge for a spin-off project entitled Phish and ChYpPS, at the Dialysis Unit, Addenbrookes’ hospital and at a series of events on Parker’s Piece. Surveys and interviews showed tools like this have potentially significant impact in terms of health, wellbeing and loneliness, all current national and international societal challenges. Boredom and isolation are known issues in clinical settings, and it is well-documented that intellectual stimulation and active entertainment (i.e. games, arts and crafts/creative play as opposed to passive entertainment like TV) improve the wellbeing and recovery time of many patients. (APPG 2017; Uwajeh & Timothy 2016; Corrigan et al 2017). MiaB would be an excellent contribution to these settings, allowing accessible but stimulating education and entertainment. Furthermore, the nature of the acrylic MiaB and 3D printed objects mean that they can also be sanitised easily to avoid cross-contamination.

Moving forward, the processes outlined above should provide ample opportunity for expansion. It is anticipated that we will be able to iron out a number of design and distribution flaws so that the creation of further collections would be significantly streamlined for future researchers. In this vein, a document was produced outlining best practice for copy creation and recording. Possible themes for further boxes imagined by the current CEEFs included: LGBTQI+/Bridging Binaries, Climate Change, Medieval Animals, Macclesfield Psalter, Ancient Mediterranean, ‘Hare’ & Makeup: Animals in Ancient Cosmetics.

The final strand for the original project plan was the creation of boxes which specifically cater for (and encourage) visits to the museum: ‘Countdown to Cambridge’/’Big Boop’ boxes. The visitor would receive a small 3D replica of a standout piece from the Museum’s collection and, when arriving at the museum, are encouraged to ‘boop’ their Buddy on one of the boxes installed within the gallery where the original object is held. Because the Buddy would be registered to you (via individually coded NFC stickers), the MiaB would be able to greet visitors by name.

This project has demonstrated that there may be viability for a museum subscription box. The materials here are cost-effective, and readily available online or through local producers. Content concepts are, indeed, almost limitless. Although somewhat time-consuming to design and assemble, such boxes could form part of any major exhibition’s promotional materials. Aside from such pragmatic concerns, the outcomes of this small pilot study have also demonstrated the possibility of engaging wider audiences, in particular those who might be remote from the museum. The major sticking point in this process is the availability and cost of MiaB hardware; although they come at a reasonable price (£249 at time of writing - https://shop.museuminabox.org/collections/frontpage) it is not a figure that many can afford.

Acknowledgements

The CEEF 3D team would like to acknowledge the roles played by many colleagues throughout this project; Dr Joanne Vine, Clare Cambridge, Will Wilson, Colin Yaxley, Dom Hill, Julia Wilson, Tom O’Hanlon, James Andrews, Helena Rodwell, Julie Dawson, Kerry Wallis, Liz Irvine, Helen Strudwick, Vicky Avery, Anastasia Christophilopoulou, David Evans, Andrew Bowker, and Georgina Doji.

They would also like to thank Cambridge Art Makers, the AHRC, UKRI GCRF, AHIF, CHRG, Sabah Abd el-Raziq and colleagues at the Egyptian Museum Cairo, Sara Hany Abed, Geoffrey Killen, Gavin Toomey, Patricia Wheatley, Hannah Platts, Julianne Piggott, Richard Rex, Katharine Fry, Philo Van Kemenade and the Mozfest Arts and Culture team, our partners Steve Dey (TS3D), George Oates and Charles Killick (MiaB) and Eugene Ch’ng for his patience with us as we meandered towards finishing this article.

Bibliography

- Adamopoulou, A. and Solomon, E. (2016) Artists-as-Curators in Museums: Observations on Contemporary Wunderkammern. THEMA, issue 4, 35-49.

- Adler, C. & Johnsson, E. (2006) Telling Tales: A Guide to Developing Effective Storytelling Programmes for Museums. http://www.crickcrackclub.com/MAIN/TELLINGTALES.PDF Accessed 15 December 2019

- AHRC. (2018) “AHRC’s Heritage Strategic Priority Area: Future Directions” https://ahrc.ukri.org/documents/strategy/heritage-strategy/ Accessed 15 December 2019

- APPG (2017) All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing Inquiry Report Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing, 2nd ed https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/Publications/Creative_Health_Inquiry_Report_2017_-_Second_Edition.pdf Accessed 15 December 2019

- Bacci, F., and Pavani, F. (2014) "First Hand," Not "First Eye" Knowledge: Bodily Experience in Museums. In Levent, N., & Pascual-Leone, A (eds) The Multisensory Museum: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Touch, Sound, Smell, Memory, and Space. (pp 17 - 22 ) Rowman and Littlefield, Plymouth, UK.

- Bedford, L. (2001) Storytelling: The Real Work of Museums. Curator: The Museum Journal, January 2001, Vol.44(1), 27-34 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2001.tb00027.x

- Bevan, A., Pett, D., Bonacchi, C., Keinan-Schoonbaert, A., Lombraña González, D., Sparks, R., Wexler, J. and Wilkin,N. (2014) Citizen archaeologists. Online Collaborative Research About the Human Past Human Computation 1.2, 183-197 (2014) https://doi.org/10.15346/hc.v1i2.9

- British Museum (2008) Touching History: An Evaluation of Hands On Desks at The British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/Hands%20On%20Report%20online%2030-12-2010.pdf Accessed August 12, 2019.

- Cambridgeshire County Council. (2016) Wisbech 2020 Baseline Evidence Profile https://cambridgeshireinsight.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Wisbech-2020-Baseline-Evidence-Profile-2016.pdf Accessed 24/10/2019

- Candlin, Fiona (2008) Museums, modernity and the class politics of touching objects. In Chatterjee, H. (ed.) Touch in Museums: Policy and Practice in Object Handling. (pp 9-20) Oxford, UK: Berg

- Classen, C. (2005) Touch in the Museum. In Classen, C. (ed) The Book of Touch (pp 275-288) Oxford, UK: Berg

- Coates, C. (2019) How are Some of the World’s Best Known Museums Doing Amazing Things with 3D Printing? https://www.museumnext.com/article/how-museums-are-using-3D-printing/ Accessed August 13, 2019

- Cooper, C.L. (2012) The Antiquities Department Takes Shape. The Fitzwilliam in the Early Twentieth Century. Journal of the History of Collections, vol. 24 (3), 347-367 (2012) https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhr036

- Cormier, B (ed) (2018) Copy Culture: Sharing in the Age of Digital Reproduction London: V&A Publishing

- Corrigan C., et al. (2017) The Perception of Art among Patients and Staff on a Renal Dialysis Unit Irish Medical Journal, Vol. 110, No. 9, 632 (2017). http://hdl.handle.net/10147/622629

- Dawson, J. (2019) How to make an Egyptian coffin: the construction and decoration of Nespawershefyt’s coffin set. Cambridge: Fitzwilliam Museum

- DCMS. (2018) Policy Paper: Culture is Digital. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/culture-is-digital Accessed 15th December 2019

- Dey, S. (2018) Potential and limitations of 3D digital methods applied to ancient cultural heritage: insights from a professional 3D practitioner.” In Wood, R & Kelley, K (eds) Digital Imaging of Artefacts: Developments in Methods and Aims Oxford: ArchaeoPress

- Di Giuseppantonio Di Franco, P., Camporesi, C., Galeazzi, F., and Kallmann, M. (2015) 3D Printing and Immersive Visualization for Improved Perception of Ancient Artifacts. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 24(3) 243-264 (2015) https://doi.org/10.1162/PRES_a_00229

- Fitzwilliam Museum. (2019) Sensual Virtual https://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/news/sensualvirtual Accessed November 1 2020

- Galvin, E. and Wexler, J. (In Press) “Hacking the Collections: Making Digital Objects Accessible and Available to Wide Audiences”. In L. Goldstein and E. Watrall (eds.) Digital Heritage and Archaeology in Practice. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Gill, D. (2018) Winifred Lamb: Aegean Prehistorian and Museum Curator. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Katifori, A, Perry, SE, Vayanou, M, Pujol, L, Kourtis, V & Ioannidis, Y. (2016) Cultivating mobile-mediated social interaction in the museum: Towards group-based digital storytelling experiences. MW2016: Museums and the Web 2016.

- Levent, Nina S., and D Lynn McRainey (2014), Touch and Narrative in Art and History Museums. In Levent, N., & Pascual-Leone, A (eds) The Multisensory Museum: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Touch, Sound, Smell, Memory, and Space. (pp 61-82) Rowman and Littlefield, Plymouth, UK.

- Lubar, S. (2018) “Cabinets of Curiosity: What They Were, Why They Disappeared, and Why They’re So Popular Now”. https://medium.com/@lubar/cabinets-of-curiosity-a134f65c115a Accessed 16 December 2019

- Mendoza, N. (2017), “The Mendoza Review: an independent review of museums in England” DCMS available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/673935/The_Mendoza_Review_an_independent_review_of_museums_in_England.pdf

- Morris, C., Peatfield, A. and O’Neill, B. (2018), ‘Figures in 3D’: Digital Perspectives on Cretan Bronze Age Figurines. Open Archaeology 4: 50-61. https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2018-0003

- National Conversation (2017) National Conversation http://nationalconversation.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/March-Report.pdf Accessed 24 October 2019

- Oates, G. (2018) If the Pilot was Wildly Successful, What Might that Look Like for You?’ https://museuminabox.org/if-the-pilot-was-wildly-successful-what-might-that-look-like-for-you/ Accessed 4 November 2010

- Oates, G. (2019) Technology is a Tool, Not Our Master https://museuminabox.org/technology-is-a-tool-not-our-master/ Accessed 30 August 2019

- Perry, S. (2019) The Enchantment of the Archaeological Record. European Journal of Archaeology 22(1) https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2019.24

- Pett, D. (In press) “Digital Humanities and The British Museum: A Short Lived Experiment?” (In Goldstein, L. & Watrall, E. (eds.) Digital Heritage and Archaeology in Practice. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.)

- Pett, D., Vine, J., Wexler, J., Cooper, C., Glen, A., Pitkin, M. (2019a) “Creative Economy Engagement Fellowship website” https://creative-economy.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/ Accessed 5 November 2020

- Reilly, Paul (2015) Additive Archaeology: An Alternative Framework for Recontextualising Archaeological Entities. Open Archaeology 1(1) https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2015-0013

- Stutz, L.N. (2018) A Future for Archaeology. In Defense of an Intellectually Engaged, Collaborative and Confident Archaeology, Norwegian Archaeological Review, 51:1-2, 48-56, https://doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2018.1544168

- Tringham, R. (2018) A Plea for a Richer, Fuller and More Complex Future Archaeology. Norwegian Archaeological Review 51(1-2) 57-63. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2018.1547920

- Tringham, R. (2019) Giving Voices (Without Words) to Prehistoric People: Glimpses into an Archaeologist’s Imagination. European Journal of Archaeology 22 (3) 338-353 https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2019.20

- Uwajeh, P. and Timothy, I. (2016) Visual Art And Arts Therapy For Healing In Hospital Environments. International Journal of Management and Applied Science (IJMAS) , Volume-2,Issue-2 159-165 https://dx.doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2010.100256

- Vayne, J. (2010) Wonderful Things, Learning with Museum Objects. MuseumsEtc.

- Wexler, J. (2016). Ancestors in the Rock: A New Evaluation of the Development and Utilisation of Rock-cut Tombs in Copper Age Sicily (4000–3000 Cal BC)." In Nash, G. and Townsend, A. (eds) Decoding Neolithic Atlantic and Mediterranean Island Ritual 187-201. Oxford; Philadelphia: Oxbow Books http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvh1dwb7.17.

- Wexler, J., Bevan, A., Bonacchi, C., Keinan-Schoonbaert, A., Pett, D. & Wilkin, N. (2015) Collective Re-Excavation and Lost Media from the Last Century of British Prehistoric Studies Journal of Contemporary Archaeology, Media Archaeology Forum, Volume 2(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1558/jca.v2i1.27124

- Wilson, P.F., Stott, J., Warnett, J., Attridge, A., Smith, M. & Williams, P. (2017) Evaluation of Touchable 3D-Printed Replicas in Museums. Curator The Museum Journal, Vol. 60 No. 4 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/cura.12244

- Wong, A. (2015) The Whole Story, and Then Some: ‘Digital Storytelling’ in Evolving Museum Practice https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/the-whole-story-and-then-some-digital-storytelling-in-evolving-museum-practice/ Accessed 16 December 16 2019