The 1913 annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (now known as the British Science Association) initiated a search for records of "all the metal objects of the Bronze Age in the Museums and Collections of the British Isles." The resulting National Bronze Age Index (NBAI) was intended to help answer major questions about the character of ancient Britain. A hundred years later, the great potential of the NBAI has been stretched even further through 'MicroPasts', an Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded digital project led by the Institute of Archaeology (University College London) in partnership with the British Museum.

In the shadow of the First World War, the archaeologist Harold Peake had set to work on the index, posting hundreds of letters to curators and collectors and carefully processing their replies, sketches, and descriptions. One important correspondent was Edward ('Ben') Cunnington (1861-1950), the curator of Devizes Museum, who, together with his archaeologist wife, Maud, excavated some of the most famous ancient monuments in Britain. His letter of April 1916, posted from the headquarters of the 68th (Welsh) Division with whom he served, sums up the mood of frustrated goodwill towards Peake's venture:

'I fear it will not be possible to do anything in the matter until the War is over and we are allowed to retire to civil life again . . We both are longing to have a turn at archaeology again but will have to wait…'

The Cunningtons would lose their only son, Edward, in the war before resuming archaeology and making valuable contributions to Peake's index in the following years. It is humbling to read these polite letters relating to small matters of ancient metalwork as war broke out and raged.

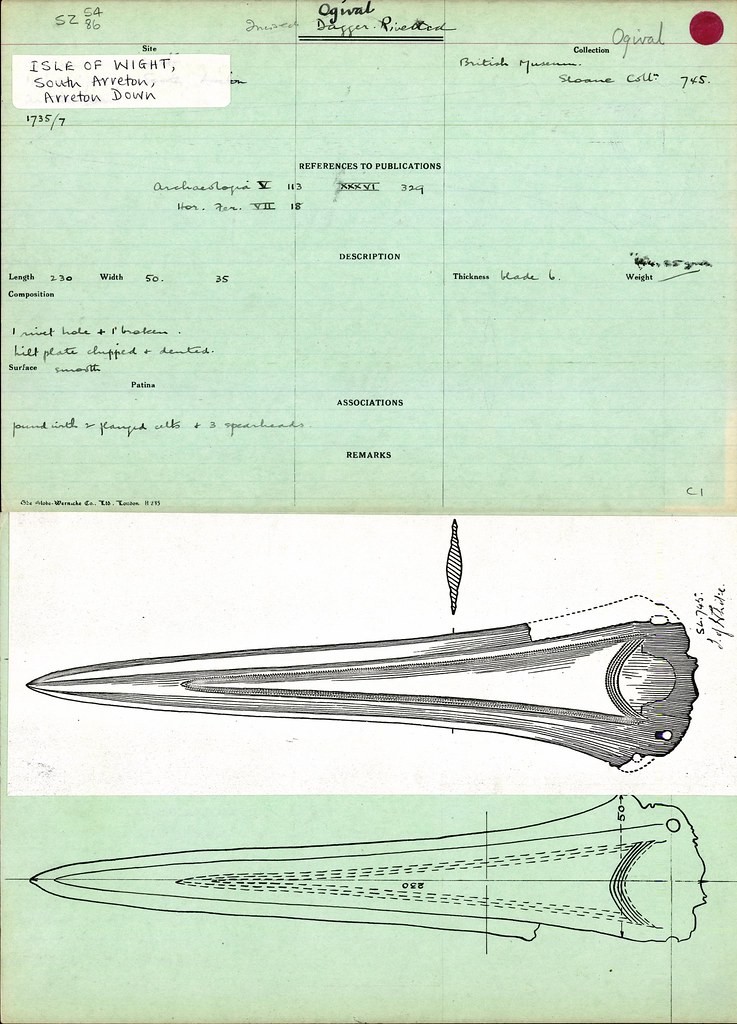

Today the index is kept at the British Museum, having been transferred there in the 1930s. Additions continued to be made by British Museum staff until the 1980s, resulting in a large corpus of double-sided index cards (estimated at over 30,000), Converting these entries into a digital format to achieve the widest possible reach is in keeping with the NBAI's initial aims and is a fitting tribute to the diligent work of all those who helped to compile it.

Now the MicroPasts project has given us a platform that provides an innovative online space for the creation of archacological data via a technique dubbed 'crowd-sourcing". Aiming to enable the public to generate high-quality archaeological data, which can be freely accessed and reused by all, the project has focused on tasks such as the transcription of old archives and field notebooks and the production of 3D models. Throughout the history of archacology as a discipline, the role of the volanteer has been vital to the success of many projects, but the creation and guardianship of the resulting data has generally remained in the hands of the specialists. The MicroPants project hopes to change this.

Other areas of the British Museum's rich archives have also benefited. The "List of Palaeolithic Implements", meticulously recorded by Worthington G. Smith (1835-1917), is a formative archival resource in the history of

British Palacolithic archaeology. It has now been transcribed with public contributions to the project and has contributed to a Leverhulme Trust-funded research project on the subject.

Alongside these transcriptions, the project has also created 3D models of objects from the British Museum's collection. This uses a low-cost technique called Structure-from-Motion (SFM), where multiple digital photographs are collected and merged into a 3D model. Photographs were uploaded and our contributors were invited to draw around the outside of the object and submit their 'photomask'. These masks were then read using computer scripes, and several of our trained volunteers produced the models (a transferable and easily learnt skill) using specialist software. The majority of models have been generated with the aid of volunteers.

This system allows the 3D models of museum objects to be created and examined in the round anywhere in the world. Several models have been annotated to provide 'guided tours' of the key features of the objects, written by curators. The models can be printed in a variety of materials and used for handling in schools and at home, even for reuse in Virtual Reality environments. The aim has been to take research material until now accessible only to a small number of researchers and make it available to the internet-enabled world at large.

MicroPasts is also trying new types of crowd-sourcing with a variety of institutions with close ties to the British Museum. Partnerships have been forged with the Egypt Exploration Society to make transcriptions of excavation records from multiple seasons at Amara West and Amarna. The Palestine Exploration Fund and the Petrie Museum have had 3D models produced on their behalf, while University College London special collections collaborated on tagging photographs. There are opportunities for people of all abilities to get involved with the Museum's work-new skills can be learnt, archaeological interest can be piqued and contributions are greatly valued by the curatorial staff involved. This is a project that aims to further the Museum's mission: it takes the Museum in London from Britain to the World, all at the click of a series of buttons or through the transcription of a few lines of text. You may wish to try it for yourself, you never know what gems you might discover in archival materials.